|

By Dr. Biegel |

Click here to download printable PDF piano score (free)

Click here to purchase bound score from Amazon.

Commentary

|

Nearly 40 years ago, in my final year at Cornell University, I conceived the purely-theoretical idea that it might be possible to create “12 tone” music which actually sounded good. What would be necessary, I reasoned, would be to reject the Schoenberg-Webern method of arbitrarily defining a rigid 12-tone “row” and manipulating it exclusively by means of artistically-constricting, non-musical mathematical formulae, and to employ instead special rows which stepped through the 12 tones of our musical scale in an orderly fashion. This approach to music might be the subject of an entire book, and is quite beyond the scope of this brief commentary. Suffice it to say that the endeavor became a life-long pursuit, but one which, however, has only borne fruit in recent years. Three Blind, Twelve-Tone Mice, although not “12 tone” in any rigid, formalized way, is nevertheless totally dependent upon the principles which emerged during the above-referenced protracted study of our 12 tone musical scale. There came a time when it occurred to me that it might be possible, with some effort, to create a theme-and-variations on the familiar melody of “Three Blind Mice”, starting in the key of C major, and serially resetting it to harmonies in all 12 possible musical keys, without changing any notes of the original C-major melody. My intention, at the outset, was to move retrograde through the 12 keys by the cycle of “perfect fourths”, i.e., the keys of C-G-D-A-E-B-F#-C#-Ab-Eb-Bb-F and, perhaps, to finish with a reprise in some alternative form of the key of C. (The reason the piece moves retrograde through this scale, rather than anterograde, is that the early retrograde keys, i.e., G-D-A, etc., are closer in sound and spirit to C major than the early anterograde keys of F- Bb-Eb, etc.). Although it hardly needs to be said, I should nevertheless point out, at the outset, that the word “key”, in such a setting as this, must be liberally interpreted. You simply cannot take the melody of “Three Blind Mice” in the key of C, and, for example, set it to a harmony based upon the traditional key of C# — such a thing is categorically impossible. Therefore, our definition of “key” must be broadened, to include any musical form which the ear hears as being predominantly rooted in a single bass tone, without reference to such classical concepts as “major” or “minor”. There are thus no key signatures in this work; all accidentals are written in. I presumed that the tonal nature of the project would be defined by the innate tonal nature of our musical scale, so that as the journey through the cycle of fourths progressed, we would be pushed farther and farther into the realm of atonality and perhaps even chaos, until reaching the tritone, i.e., the midpoint of the journey, from whence we would make the return journey, moving back into progressively more-familiar territory until we arrived back at the mother key of C. As anyone who has ever considered writing 12-tone music knows, a scale which progresses by the interval of a perfect fourth is exceedingly difficult for the human ear to hear as being a musically coherent collection of notes. Unlike the C-major scale, every part of which sounds like it’s in the key of “C”, the perfect fourth scale, if played in the ascending direction, starts out sounding fairly “minor”, passes through the tritone, which is nondescript, and winds up sounding “major”: |

|

The human ear has no difficulty hearing and comprehending either the beginning or the end of this scale, but hearing and comprehending them both simultaneously is exceedingly difficult. The reader who doesn’t understand this statement should try an experiment which will well-illustrate the point: Play a “C” note on the piano, then go into another room, close the door, and try to imagine the above scale in your mind, note-by-note, without losing the pitch of the C bass. Then return to the piano, sing what you think is “C”, and check it against the piano. You’ll almost surely find that your pitch has drifted at least a half-step, if indeed you have any recollection of the pitch at all. (If your pitch hasn’t drifted at least a half step, then you’re either an ear-training master, or a person endowed with perfect pitch who cannot be moved!). When performing this exercise, whether one starts on the “minor” side and moves anterograde, or on the “major” side moving retrograde, one finds that as one approaches the tritone, the sound becomes increasingly difficult to imagine, or to hear accurately in the “mind’s ear”. Beyond the tritone, only a musician with a strong background in ear training can accurately imagine the sounds on the other side of the scale without the help of an external instrument. If one attempts to define, analyze or understand the basis of this problem, one finds that it is of unfathomable depth, wherefore we shall not try to define, analyze or understand it, but merely to deal with it. For discussion purposes, I have found it convenient to treat it as if it was entirely rooted in the difficulty of “hearing”, in the mind’s “ear”, the interval between the two notes flanking the tritone, namely (in this example) D-flat and B, which constitute a musical “bridge” of sorts; i.e., a bridge from the “minor” to the “major” portions of the scale. In the absence of an external instrument, this bridge is exceedingly difficult for the human ear to cross. In my own formulation of things I refer to this bridge as “the forbidden interval”. The terminology “forbidden interval”, therefore, refers specifically to this particular musical whole step, which goes from the flatted 9th to the major 7th of any given key, while holding the bass note constant: |

|

If you play this exactly as written, it sounds harsh and dissonant. I’ve tried, literally for decades, to “train” my ear to like this sound, but it just doesn’t work. Out of context, it has no musical meaning, and it’s simply not pleasant to listen to. It needs harmony to give it meaning. But how on earth do you harmonize such a thing? In the entirety of all classical music, I know of only one single setting in which the forbidden interval is found, namely in the resolution of the so-called “Italian 6th” to the dominant, before returning back to the tonic. An excellent illustration of this may be found in Beethoven’s very 1st Symphony, 3rd movement, measures 58-60. In the figure below, the actual score is on the left, a piano reduction in the middle, and the extracted and isolated “forbidden interval” on the right: |

|

This musical setting of the “forbidden interval”, however, is of no help whatsoever as a model for the 12-tone composer, because the Db of the Italian 6th is merely a passing tone. It dances about the dominant, but has no essential melodic significance. When we attempt to use various formulae to generate 12-tone music, there exists among modern composers a universal understanding that we are somehow bound to treat all 12 notes of the scale equally, and to use them all with the same frequency and regularity. These formulae will, inevitably, force the composer into intimate contact with the “forbidden interval” in settings where the two notes are indeed essential melody notes, not merely passing tones. If one wishes one’s music to sound pleasing to the ear, one must find a way to deal with these unruly notes. But how?

Before attempting to grapple with this first issue, a second one, which approximately doubles the difficulty raised by the first one, must also be dealt with. This second issue is something I call “ta’am”, which is a Hebrew word ( Every musical interval has two forms, which I refer to as its two “ta’amim” (the plural form of the Hebrew word “ta’am”). What to call the two forms is somewhat, but not entirely arbitrary. It’s probably best to think of them as “major” and “minor”, but they can also be thought of as “sweet/sour”, “soft/hard”, or, more generically, simply “yin/yang”. This phenomenon, of two ta’amim for every musical interval, operates ubiquitously and continuously in music. It is well-illustrated by the augmented triad, which consists of a stack of two major third diads: |

|

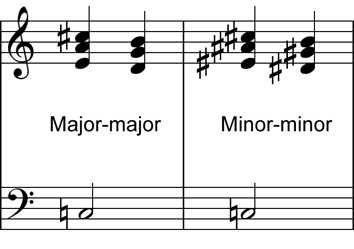

The first, consisting of the notes C and E, is the familiar major diad, which is the defining pair of notes for all the countless major triads we have been hearing continuously since infancy. I would describe its sound as “soft”, or, more functionally, simply as “major”. In contrast, the upper two notes, E and G#, in the context of the augmented chord, have an entirely different sound; one which I would describe as “hard”, or, more functionally, “minor” (you can, for example, think of the G# in the above example as having the “ta’am”, or essence of the minor 3rd note of an F minor chord in second inversion). Thus, the top and bottom diads of the augmented chord, although they are the same musical interval – 4 half-steps – have sounds which are completely different. In my own terminology system, I would say that each has a different “ta’am”. I have no clue as to what the anatomy, physiology or psychology of this duality is. It must simply be accepted as a built-in, and incomprehensible characteristic of the musical world we live in. The relevance to our “forbidden interval” is that there are, because of the two ta’amim, four forms of the interval: major-major, major-minor, minor-major and minor-minor. If you don’t have any idea what I’m talking about, here’s a bare-bones simple illustration of what I call “major-major” and “minor-minor”: |

|

The first example (“major-major”), which sounds rather dissonant and unpleasant in isolation, has little if any context in ordinary music. The second (“minor-minor”) doesn’t sound much better, but has more of an historical musical context if we consider the bass note “C” to be the major 3rd of an Ab chord. Nevertheless, neither of them look (i.e., sound) as if they have much use in the composition of music that anyone would want to listen to. So, with respect to our 12-tone theme and variations on “Three Blind Mice”, within which we are certain to encounter one or more “forbidden intervals”, as well as other non-tonal problems requiring innovative solutions, we clearly shall have our work cut out for us.

|

“Rules of the Game”

|

I regard “Three Blind, Twelve-Tone Mice” as a game, and as a challenge. Since it’s my own challenge – from myself to myself – I have therefore established my own rules. The rules are different for the two sections of the melody. The melody may be considered to consist of an “A” section (corresponding to the lyrics “Three blind mice, three blind mice, see how they run, see how they run”) and a “B” section (“They all ran after the farmer’s wife...”, etc.). The rules for the “A” section are more stringent: Rule #1: The melody must remain in the key of C throughout, and, other than in tempo, must not be significantly altered in any way. Rule #2: The “A” section must sound like the designated key, or, in the event that the musical style is not really amenable to the strict identification of a proper classical key, it must at least sound closer to the designated key than to any other. The rules for the “B” sections were more relaxed. I demanded only that they follow logically from the “A” sections, and merge seamlessly back into them. In particular, I should note that I allowed the “B” sections to modulate as they would, in accordance with the final rule: Rule #3: Above all, since this is music, which is a form of entertainment, the result must be entertaining; the entertainment taking precedence over the “academic merit”. |

Specific comments on some of the more difficult themes/variations

|

Key of G (variation #2): Going into this project, I envisioned the key of G, being the dominant, and therefore closest possible key to C, would be the easiest to work in. Actually it was the most difficult! The problem is that the 3rd melody note (corresponding to the word “mice” in “Three blind mice...”) is C, which is a suspenseful note in the key of G, demanding resolution. No resolution is possible! I could have dreamed up an alternative variation, something farther off the beaten path of traditional tonality, but I wanted the keys closest to C to sound “traditional”. My proposed solution (see measure 10) was to add the little sotto voce phrase... |

|

...after the “Three blind mice...” melody. Whether I should be charged with the crime of violating the very first of my own stated rules is a question whose answer I shall leave to the listener.

Key of F# (variation #7): In measure 60 we encounter the first of three occurrences of the above-referenced notorious “forbidden interval”. This one may be described, according to the principles I proposed earlier, as “minor-major”. The problem of dissonance, in this case, was solved by using a contrary motion chromatic left-hand figure, which somehow defused the awkwardness and unpleasant sound of the unruly interval.

Key of C# (variation #8): The opening of this variation contains the second of the three occurrences of the “forbidden interval”. Quite self-evidently, and quite literally, this is the “minor-minor” variety. The problem here is solved by “resolving” the forbidden interval into a first-inversion “A” chord. This, however, creates a new problem, namely that this procedure moves the variation strongly into the key of “A”, from whence it must be returned. Key of Eb (variation #10): In the first measure (mea 88) we find the third and last occurrence of the “forbidden interval”, this time self-evidently and literally “major-major”. As in the case of variation #7 (F#), the inherent unpleasantness of the interval was solved by judicious use of chromatic voice leading. |

|

ACKNOWLEDGMENT The composer wishes to thank Mr. Peter Homans for encouragement and critical review. If not for his encouragement, this project would probably have ended with the mp3 recording, and the printed score (available on Amazon; see above) might never have been completed. More importantly, in his insightful review of the 1st draft, he correctly pointed out that the variations in the “keys” of C# and Eb were, in the final analysis, covertly in the keys of A and C, respectively. This necessitated that they be re-written. The work, in its current form, is substantially improved because of his incisive intervention. |

© 2011

![]()